The origin of the word satin has long intrigued scholars of linguistics and textile history. The most widely accepted theory traces its derivation to the Arabic zaitun or zayton, a reference to the Chinese port city of Quanzhou.

Satin is a luxurious fabric characterized by a glossy surface and smooth texture, often associated with opulence and high social status. The term satin has been documented in various European languages, appearing as satin in French, satijn in Dutch, and seta in Italian. While its phonetic structure varies slightly across languages, its etymological origins are widely attributed to medieval Arabic influences, reflecting the linguistic and commercial interconnectedness of Eurasian civilizations.

The Arabic Connection: “Zaitun” and the City of Quanzhou

Known in earlier times as Cìtóngchéng, Quanzhou played a pivotal role in medieval trade, particularly in the dissemination of luxurious silk textiles. The city’s historical nickname, tsheH dwung dzyeng or Cìtóngchéng, meaning “Coral Tree City” or “Tung Tree City,” is attributed to Liu Congxiao (906–962 CE), a general during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907–979 CE), who encouraged the extensive planting of the Cìtóng (Erythrina variegata) or Tung tree. This article explores the linguistic transformation of satin, analysing its phonetic evolution through intercultural exchanges and its connection to the rich commercial history of the maritime Silk Road.

Closeup of a pair of women’s trousers ‘Șarwāl’ from Oman with satin stitch embroidered ‘bu tayrah’ motif popular in both Iran and the Arabian Peninsula believed to be of Chinese and/ or Central Asian origin; Oman, c. mid 20th century; Acc. No. ZI2023.501028 OMAN

A pair of women’s trousers ‘Șarwāl’ from the UAE with satin stitch embroidered ‘bu tayrah’ motif popular in both Iran and the Arabian Peninsula believed to be of Chinese and/ or Central Asian origin; UAE, c. 1989; Acc. No. ZI1989.500726 UAE

One of the strongest etymological theories links the word satin to the Arabic zaitun or zayton, a term used by medieval Arab traders to describe the bustling port city of Quanzhou. Located in Fujian Province, Quanzhou was a key maritime hub during the Song (960–1279) and Yuan (1271–1368) dynasties, facilitating trade between China, the Middle East, and Europe. The city was famous for its role in the silk trade, exporting high-quality textiles, including the fabric now known as satin.

The Arabic term zaitun appears in several historical texts, including those by the famous traveller Ibn Battuta, who visited Quanzhou in the 14th century. Arab traders adopted the term as a phonetic approximation of Quanzhou’s historical nickname, Cìtóngchéng, which translates to “Coral Tree City” or “Tung Tree City.” The planting of the Tung tree was encouraged by Liu Congxiao due to its economic significance—the tree’s sap yielded Tung oil, which was extensively used for varnishing and caulking in the shipbuilding industry. Given Quanzhou’s status as a vital maritime trade centre, the presence of these trees further supported the region’s economic and commercial endeavours.

Page 148 from the book Golden Peaches of Samarkand

A linguistic shift is believed to have occurred when Chinese traders in Persia and Arabia encountered the olive tree (Olea europaea), which they referred to as qidan, a term influenced by the Aramaic zaitā (meaning “olive”). The phonetic similarity between Cìtóng and qidan may have contributed to Persian and Arab merchants designating Quanzhou as Zaitun or “Olive Town.” Over time, this designation became synonymous with the high-quality textiles produced in the city, further embedding the term into the linguistic fabric of trade.

Quanzhou as a Centre of Maritime Trade

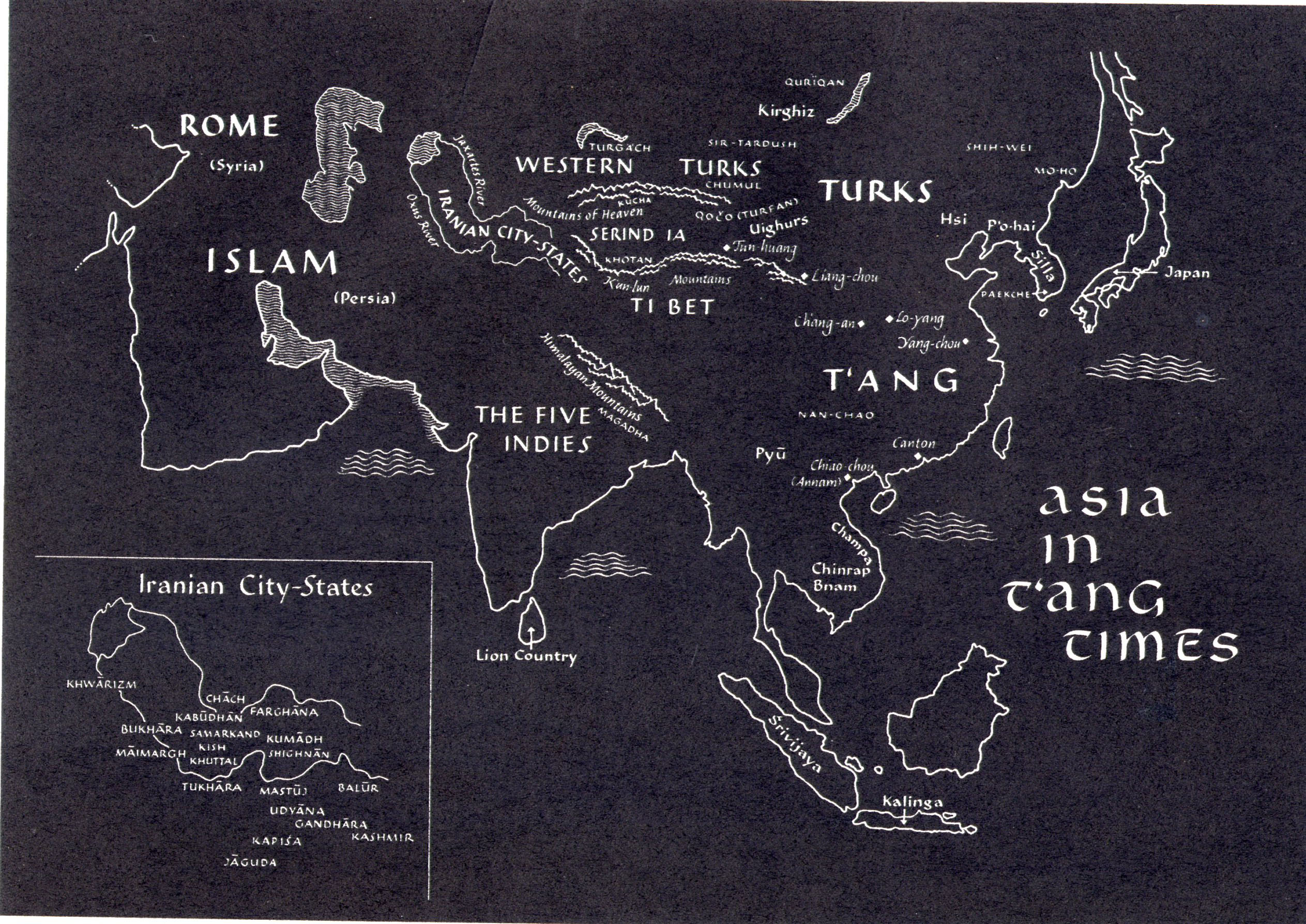

Map of Asia in T’ang times, an illustration in Golden Peaches of Samarkand

Map of Asia in T’ang times, an illustration in Golden Peaches of Samarkand

As documented in Trade, Travel, and Exploration in the Middle Ages: An Encyclopaedia by Friedman and Figg, Quanzhou functioned as a crucial maritime trade centre, in 1087 CE during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE). The rapid population growth during this period led to a substantial increase in the volume of cargo passing through the port. Quanzhou’s geographically advantageous position provided access to inland cities via an extensive network of roads and waterways, further consolidating its role as a dominant trade hub.

The strategic significance of Quanzhou was further emphasized during the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368 CE). Recognizing its importance, the Mongol rulers utilized Quanzhou as a launching point for military campaigns, including the ill-fated invasions of Japan in 1281 CE and Java in 1292 CE. By the late 13th and early 14th centuries, Quanzhou had evolved into a thriving centre for international trade, attracting a significant population of foreign merchants, particularly Arab and Persian Muslims. This period of prosperity was largely facilitated by the Mongol administration’s relatively tolerant policies towards foreign traders.

Archaeological and architectural evidence from this era attests to the presence of a diverse foreign community in Quanzhou. Inscriptions on tombstones discovered in the region reveal a variety of scripts, including Syrian, Arabic, and Latin, underscoring the city’s cosmopolitan character. However, this era of international exchange came to an abrupt decline with the rise of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 CE). The new regime implemented stringent trade policies, often described as isolationist, which significantly curtailed China’s interactions with the Middle East and the broader Western world, marking the end of Quanzhou’s prominence as a global maritime trading centre.

Linguistic Evolution: From “Zaitun” to “Satin”

The transition from zaitun to satin likely occurred through phonetic adaptation as the term moved westward along trade routes. Medieval Latin texts began incorporating variations of the word, with references to “aceytuni” and “setinus” appearing in European documents from the 12th and 13th centuries. The phonetic shift can be attributed to the linguistic influences of Romance languages, which often adapted Arabic loanwords to fit their phonological structures.

As trade intensified between the Middle East and Europe, the term further evolved into its modern European forms. The Old French satin, recorded in the 15th century, closely resembles the English spelling and pronunciation we recognize today. This linguistic progression reflects the cultural and economic exchanges that defined the medieval and early modern textile industries.

Alternative Theories on the Origin of “Satin”

While the Arabic derivation from zaitun remains the most widely accepted theory, an alternative hypothesis suggests that the word satin originates from the Latin sēta, itself derived from saeta, which traces its roots to the Proto-Indo-European sh₂ey- meaning “to bind” or “to fetter.” This etymological connection is potentially significant, as the satin weave is characterized by a unique structure in which four or more weft yarns float over a single warp yarn, or vice versa. These “floats,” which refer to missed interlacings where the warp yarn lies on top of the weft in a warp-faced satin, contribute to the fabric’s distinctive smoothness and high sheen. Unlike other weaving techniques, the reduced scattering of light across satin’s surface results in an enhanced reflective quality, making the fabric exceptionally lustrous.

Typically, satin employs a warp-faced weave, where the warp threads predominate on the surface, though variations exist that utilize a weft-faced configuration. Proponents of the Latin origin theory argue that the term satin could have emerged independently in Western Europe due to the technical and structural properties of the fabric. Nevertheless, this theory remains a minority view, as the preponderance of historical and linguistic evidence supports the Arabic-Chinese derivation linked to Quanzhou’s prominence in the medieval silk trade.

The etymology of satin provides a compelling illustration of how language evolves through commercial and cultural interactions. The fabric’s name, rooted in the Arabic zaitun, ultimately derives from the Chinese city of Quanzhou, historically known as Cìtóngchéng. The linguistic resemblance between Cìtóng and qidan may have further contributed to the adoption of Zaitun as a name for the city by Persian and Arab merchants. This linguistic journey underscores the profound impact of trade networks on global language development, reinforcing the enduring legacy of the maritime Silk Road. Further research into historical trade records and linguistic adaptations may yield even deeper insights into the intricate pathways of word transmission across civilizations.