Building upon the preceding segment, this installment continues the exploration of traditional Moroccan urban male dress by turning to the next layer of headwear. The multiplicity of head coverings – ranging in form, material, and method of wear – offers valuable insight into the visual language of socio-economic stratification within Moroccan society. These layers were not merely functional or aesthetic additions; rather, they served as coded signifiers of status, profession, regional origin, and cultural affiliation. In addition to headwear, this discussion will examine the various scarves and torso drapes, or mantles, that complemented male attire. These textile elements, while contributing to the ensemble’s physical structure, also operated as expressive media through which individuals negotiated identity and social belonging in the urban Moroccan milieu.

Headwear (contd):

In the preceding segment, the discussion focused on the diverse range of caps and head coverings traditionally worn by Moroccan men in urban contexts. These included the iconic fez, emblematic of Moroccan identity; the regionally favoured chéchia; and the more widely disseminated tāqīyah, prevalent across the broader Arab world. However, the deeply embedded cultural practice of layering – central to the construction of male dress – meant that such foundational headwear items were rarely worn in isolation. Instead, they were frequently enveloped in additional textiles, each distinguished by its material composition, method of wrapping, and symbolic connotations. These layered wrappings not only enhanced the visual complexity of the ensemble but also served as markers of individual identity, social positioning, and functional purpose within the intricate fabric of Moroccan urban life.

Rezza and ‘Imamah

An Sudanese men’s ‘Imamah; Title: Turban, Sudan, c. 21st century; Source: The Zay Initiative; Link

An Sudanese men’s ‘Imamah; Title: Turban, Sudan, c. 21st century; Source: The Zay Initiative; Link

As previously noted, the fez is frequently wrapped with a white cloth—most commonly white muslin—by men of moderate means, forming a headpiece known as the rezza del qaleb, or “turban formed on a mould.” This designation refers to the method of construction, wherein the cloth was meticulously wrapped around a fez that had been placed atop a wooden mould. The process, typically carried out by skilled practitioners – often professional hairdressers – required a careful adherence to established techniques, including the moistening of the fabric to ensure it conforms smoothly to the contours of the underlying cap. While the rezza del qaleb was widely adopted by the urban middle classes, it held particular resonance among the educated elite, especially men of letters and intellectuals, for whom it signified cultural refinement, and scholarly identity.

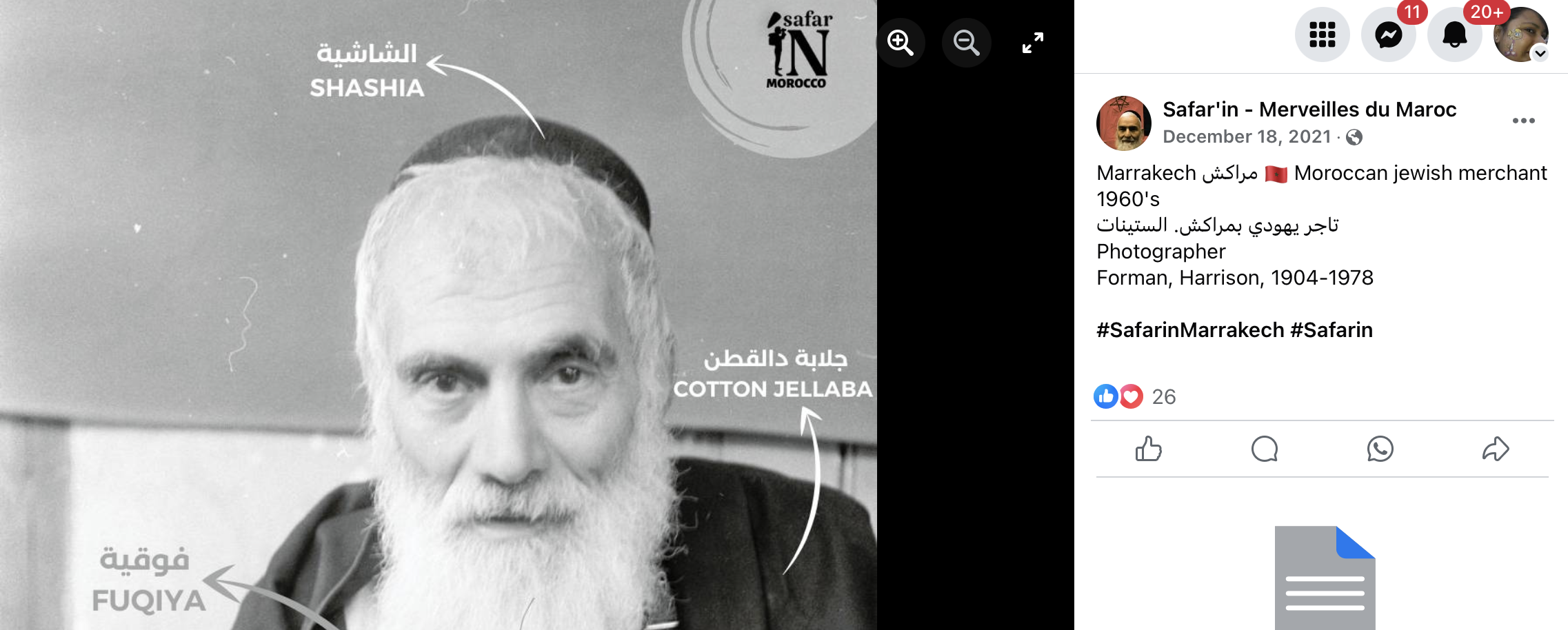

Screenshot of a man wearing the rezza del qaleb as posted in a photograph uploaded by user @ Safar’in – Merveilles du Maroc; Link

Screenshot of a man wearing the rezza del qaleb as posted in a photograph uploaded by user @ Safar’in – Merveilles du Maroc; Link

The rezza del qaleb was not only associated with middle-class urban men but also formed a standard component of the official attire of imperial and royal functionaries, or makhzin, within the Moroccan court. It was commonly wrapped around the chéchia, reinforcing its visual and symbolic prominence within administrative and ceremonial contexts. Among higher-ranking officers, the rezza was frequently accompanied by an additional turban, the volume of which was proportionate to the wearer’s status and hierarchical position. As observed by Jean Besancenot, in the case of senior officials, this elaborate headdress could involve the use of two separate textiles, each measuring approximately forty yards in length, resulting in a visually imposing and symbolically charged ensemble.

Screenshot of a man wearing the chéchia (spelled ‘SHASHIA’) as posted in a photograph uploaded by user @ Safar’in – Merveilles du Maroc; Link

Screenshot of a man wearing the chéchia (spelled ‘SHASHIA’) as posted in a photograph uploaded by user @ Safar’in – Merveilles du Maroc; Link

While the rezza del qaleb served as the foundational wrapping, it was often further encased in an additional layer of voluminous muslin known as the ʿimamah. Widespread across the Arab world, the ʿimamah – typically composed of lightweight cotton or similar breathable fabric and extending up to six meters – denoted not only a specific type of turban but also the textile used to form it. Its use among elite officials in Morocco reinforced broader regional continuities in dress, while also distinguishing the wearer within the local structures of authority, piety, and erudition.

Scarfs and Other Torso Drapes:

The following section offers a brief examination of scarves and shoulder mantles that are customarily draped around the head and upper torso. These individual textile elements functioned as integral components within a broader system of vestiary layering, frequently worn in conjunction with other garments to form cohesive ensembles. Far from being merely decorative, these draped accessories contributed to the modulation of formality, seasonality, and social distinction, and were often governed by established conventions of material, proportion, and method of wear.

Chane/Shānah, Ksā’ and Hāyīk

The chane (شانة) is a small, lightweight scarf traditionally worn by older men, typically draped around the head and neck. Constructed from fine wool or cotton, it served both practical and symbolic functions, offering modest protection from the elements while simultaneously reflecting age-associated conventions. In addition to the chane (شانة), prominent urban men of distinction often adorned themselves with a ksāʾ (كساء), a long rectangular cloth made of light wool, frequently featuring striped motifs woven along the weft with supplementary silk bands forming part of the decorative background. These textiles typically measured between five to six meters in length and approximately 1.8 meters in width (selvedge to selvedge), enabling them to be worn as a mantle draped over the head and shoulders in accordance with specific, codified customs of wear.

The ksāʾ (كساء) is generally regarded as an evolution of the hāyīk (حايك), a traditional Amazigh draped garment. The hāyīk (حايك), believed to be of Arab-Andalusian origin, comprised large white rectangular panels of fabric that were fixed in place at the shoulders and upper torso using decorative fibulae. Worn across both rural and urban contexts, the hāyīk not only influenced subsequent forms of draped mantles like the ksāʾ(كساء), but also contributed to the broader lexicon of North African dress, where distinctions of class, age, and ethnicity were often encoded through textile selection, dimensions, and modes of draping.

A draped full body unisex mantle or hāyīk of Moroccan origin; Title: Woven linen and camelid fibre cloak, Morocco, c. late 19th– early 20th cxentury; The Zay Initiative

A draped full body unisex mantle or hāyīk of Moroccan origin; Title: Woven linen and camelid fibre cloak, Morocco, c. late 19th– early 20th cxentury; The Zay Initiative

Thus, the headwear and draped textiles examined in this section – ranging from structured caps such as the fez, chéchia, and tāqīyah, to more fluid accessories like the chane (شانة) and ksā’ (كساء)– illustrate the complexity and cultural specificity of male adornment practices in traditional urban Moroccan dress. These items, while often regarded as supplementary, occupy a critical position within the sumptuary hierarchy, functioning as visible markers of identity, age, class, and regional affiliation. Their forms, materials, and modes of use reveal a nuanced grammar of dress that is both historically embedded and socially expressive.

The subsequent segment will extend this inquiry into the domain of lower-body accessories, with particular attention to waistbands and footwear. These items, including various forms of the hizām – حزام– (belt or sash) and traditional leather slippers and other footwears, further articulate the performative and symbolic dimensions of dress, providing insight into the ways in which Moroccan men navigated social boundaries, aesthetic expectations, and embodied practices through the everyday act of getting dressed.