The Egyptian Asyut shawl, or Asyuti, gained significant prominence in the late 19th and early 20thcenturies, particularly within Western fashion circles. This period coincided with a peak in Western colonial expansion and an associated fascination with the East, often referred to as Orientalism. The Asyuti, characterized by its intricate hand-embroidered metallic thread patterns on lightweight cotton or linen, became a symbol of exotic elegance and cultural mystique. Its rise to fame can be attributed to the West’s growing obsession with Eastern aesthetics and artifacts, spurred by the colonial narrative and the romanticized allure of the Orient. This fascination was reflected in various forms of art, literature, and fashion, where the Asyuti emerged as one of the coveted accessories, embodying the Western idealization of Eastern opulence and craftsmanship.

The Shawl in Light of Egyptian Culture and History

Located south of Cairo, Asyut is the largest city in Upper Egypt and serves as a central hub for Coptic Christians in the region. Historically known as ‘Lycopolis’ during the Ptolemaic Greek period, the city retains its ancient Pharaonic name, ‘Syut’ or ‘Zyut’. Due to its strategic position between Cairo and Luxor, Asyut has long functioned as a crucial trading centre, facilitating commerce between Lower Egypt and the rest of Africa. In addition, it has historically served as an important stopover for travellers and tourists.

Part of an Asyuti or tarha, Asyut, Egypt, c. 1920; Acc No ZI2018.500126.2 EGYPT; Source: The Zay Initiative

While metal thread work has been prevalent in Egypt since ancient times, both in woven as well as embroidered textiles, the history of “tulle bi talli,” or the technique of metal thread work used in making Asyutis, is relatively recent. Most scholars and experts associate tulle bi talli with the Ottoman Empire, possibly because some of the earliest examples of this technique, although not on tulle, are from the Ottoman period.

Although there is debate amongst scholars regarding the origins of talli work the most plausible perspective is that it was possibly imported from Ottoman Turkey and Turkic Central Asia, spreading widely with the expansion of the Ottoman Empire.

The earliest datable example of talli embroidery appears in the mid-16th century, associated with the son and wife of Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent. Similar techniques are found in 16th century fragments from Qasr Ibrim in Egypt. According to Egyptian textile historian Shahira Mehrez, talli already existed in the Arab world by the late 9th and early 10th centuries, as evidenced by the term ‘tāli’ appearing in significant chronicles from that period. Mehrez further notes that talli textiles are cited in records of gifts sent by Byzantine Emperor Constantine IX Monomachus to the Fatimid caliph around 1046 CE. Mehrez argues that although this might suggest a Byzantine origin, two key facts suggest otherwise. First, the gifts included turbans, a Muslim head covering unknown in Byzantium. Second, the records, meant to impress the recipients, usually often specified the origins of the presents, the absence of which in this case confirms that talli was well known in the Fatimid court.

Comparable techniques of textile embellishment involving the application of hammered metal plate have been documented across a broad geographic span, extending from the Indian subcontinent and Iran to the Levant and the Arabian Peninsula. These techniques, while regionally distinct in nomenclature and slight stylistic variation, share notable technical affinities with tulle bi talli of Egypt. Known as bādla in South Asia, tariq in the Levant, khus dozi in Iran, and naqdah in the Arabian Peninsula, these forms constitute a wider regional tradition of hammered metal plate textile ornamentation.

The proliferation of bādla in the Indian subcontinent is particularly associated with the 16th and 17thcenturies, flourishing under the patronage of Empress Nur Jahan, the chief consort of the Mughal Emperor Jahangir. In the Levant, the adoption and adaptation of such techniques were likely facilitated through Ottoman cultural influence, while in the Persian context, khus dozi arguably contributed to the development of naqdah in the Arabian Peninsula through historic trade and cultural exchanges.

Of particular interest is the South Asian attribution of bādla’s origins to Nur Jahan herself. While such claims remain anecdotal and cannot be substantiated through primary sources, they nonetheless underscore her significant role in shaping the textile arts of the Mughal court. Born into an aristocratic Persian family in Kandahar, Nur Jahan would likely have been familiar with khus dozi or similar Turkic and Turkic Central Asian textile traditions prior to her ascendancy in the Mughal imperial court. Her exposure to these practices may have informed her promotion of employing hammered metal plates in textile art of South Asia, where she played a pivotal role in its refinement and dissemination by commissioning artisans and integrating these techniques into the imperial ateliers.

This interregional trajectory not only highlights the interconnected nature of textile cultures across several regions of the world but also suggests a shared heritage of ornamental textile practices that transcends rigid geographic and political boundaries. It points to a complex history of mutual influence, patronage, and artisanal mobility.

In Egyptian cultural history, the Asyut shawl has always held significant importance. Although often referred to as “Coptic Shawls” or “Copt Scarves” by 19th century European travellers, the Asyuti transcended religious and economic boundaries. These shawls were regional specialties crafted by women from farming and working-class communities, regardless of their religious affiliations. The association with Coptic Christianity likely stemmed from a misinterpretation, as the region of Asyut and its surrounding areas have historically had a high concentration of Coptic Christians.

Highly valued by women in the agricultural community, particularly in the impoverished regions of Upper Egypt, these shawls, often used as shawls, were cherished possessions and integral components of wedding trousseaus. Reserved for significant ceremonial occasions throughout their lives, these shawls held immense sentimental and cultural value.

The Shawl and the West

The Western connection of the Asyut shawl is indeed fascinating. While their prominence during the Art Deco era and their significant influence on flapper dresses might suggest that they gained popularity in the first quarter of the 20th century, this assumption is incorrect. It is true that their presence in dance costumes on stages in urban centres across Egypt during the early 20th century, coupled with the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922, spurred European travellers and Western society to incorporate Egyptian aesthetics into the Art Deco movement. However, it would be presumptuous to assume that the integration of these glittering pieces into Western culture occurred solely post-industrialization.

Asyut shawls had already made an impact in Europe following Napoleon’s conquest of Egypt and Syria (1798-1801). By circa 1809, shawls made in Asyut for local use featured talli embroidery on cotton or flax grounds were making its way to the west. One of the oldest surviving examples of talli on net or tulle dates back to circa 1810-11, from the collection of Empress Josephine of France. Modern tulle became widely available in the early 19th century after English inventor John Heathcoat invented the bobbinet machine in 1809. Originally called “English Net,” the fabric became widely known as “tulle” after the lace-making centre in France bearing the same name.

Tulle or “English Net” became a staple for European travellers to Egypt since the French conquest. With the Industrial Revolution in full swing, steam-powered boats—introduced around 1787—and steam locomotives—developed and improved by circa 1775—made travel to distant regions more accessible.

The 19th century Western travellers on the Nile had three primary modes of travel: sailboat, steam-powered paddle boat, or train. The traditional method, exploring Egypt by sailboat, required tourists to allocate up to 40 days for a round trip from Cairo to Luxor via Asyut, as advised by numerous travel guides. This was the slowest and most expensive mode of travel. Steamboats, by contrast, were the most popular means of traveling the Nile. Paddle-wheel riverboats became common on the Nile after the 1870s, offering set tours that stopped at major destinations such as Memphis, Abydos, Dendareh, Thebes, and Luxor. Asyut was a required stop on every tour for picking up provisions, sightseeing, and occasionally accommodating tourists making train connections.

Tour books were indispensable for foreign travellers to Egypt, providing crucial guidance on necessary precautions against various illnesses that could result in lasting or permanent conditions. One such illness was trachoma which was caused by bacteria. A highly contagious ailment it could easily spread amongst through direct contact and by flies. Other common ailments of the time included diarrhoea, malaria, and other fevers transmitted by mosquito bites.

Travelers were advised to bring mosquito nets, and women were encouraged to wear scarves to protect themselves from these insects. Consequently, transparent bobbinet tulle became an essential item in the luggage of Western travellers. This necessity effectively introduced the fabric to Egypt, marking its initial integration into the region.

The remarkable qualities of English bobbinet made it an exceptional substitute for the traditional Asyut shawl. Unlike the limited width of traditional cloth, bobbinet or tulle fabric could be manufactured in much wider dimensions. Furthermore, its construction featured a robust yet flexible hexagonal structure, achieved by wrapping or twisting diagonal weft threads around a sturdy warp framework. This design not only allowed the fabric to stretch and drape elegantly but also ensured it rarely frayed, enhancing its durability and functionality.

Close up of an Asyuti or tarha, Asyut, Egypt, c. 1920; Acc No ZI2018.500126.2 EGYPT; Source: The Zay Initiative

Although Asyut shawls were widely prevalent in Egypt and were locally known as tarha, they represented a form of cultural folk art—a traditional local embroidery skill transmitted from mother to daughter and shared among friends and family members. Consequently, this craft was often undocumented by Western historians in their travel journals. It was not until the late 19th century that travellers began to document the shimmering shawls of Asyut in their travel journals. However, these accounts were notably devoid of visual references. Tourists found it exceedingly difficult to photograph local women, rendering a significant gap in the visual documentation of these cultural artifacts.

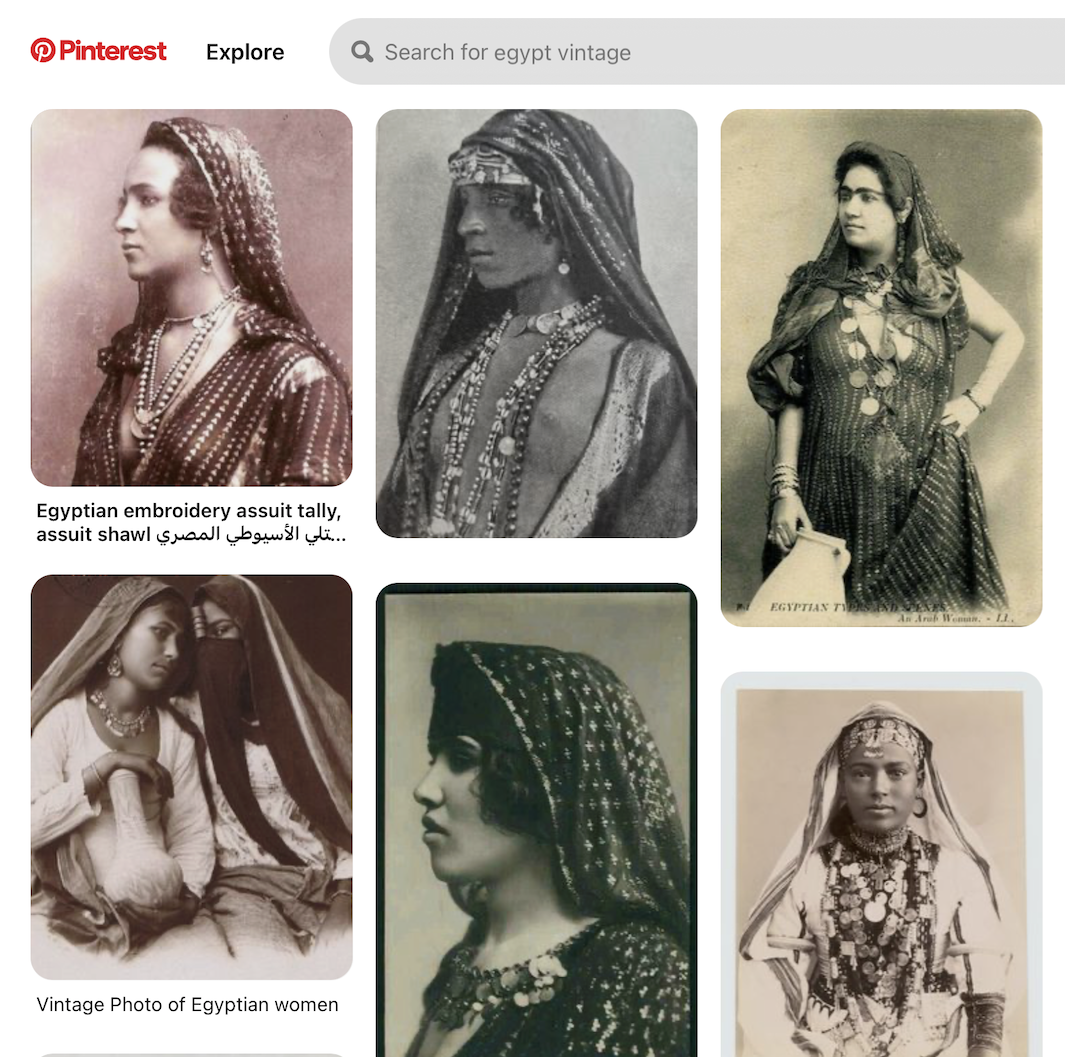

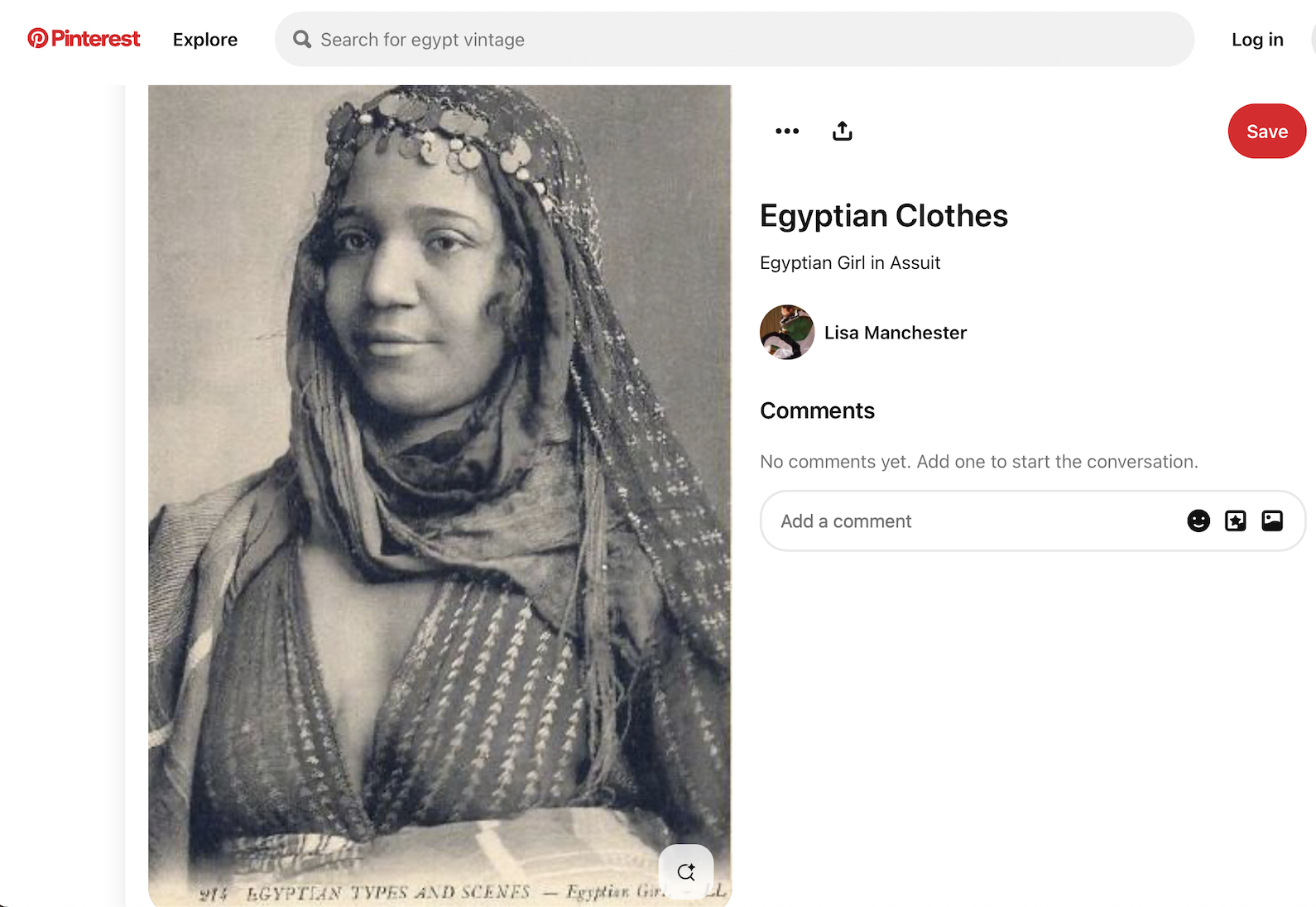

Upon arriving in Egypt, Western tourists typically spent a few days in Cairo before embarking on their journey down the Nile. During this period, tourists commonly shopped for local wares and regional crafts. Among the popular purchases were postcards, which served as souvenirs or gifts. These postcards often featured scenic views as well as images of women and girls in traditional attire. There were generally two types of postcards available in Egyptian markets: those with an ethnographic focus and others depicting more erotic images of showgirls and musicians, which were primarily targeted at male tourists.

Screenshots of images of samples of ethnographic postcards from Egypt on Pinterest, by various users. Source: Pinterest

The distribution of these postcards ultimately ignited Western interest in Asyut shawls, leading to their acquisition as souvenirs. Tourists frequently purchased these shawls during their travels to ward off flies and mosquitoes, subsequently bringing them back as unique cultural and exotic artifacts. Their compact size and durability made them damage resistant and distinguished them from other, less reliable items.

Thus, the introduction of the Asyut shawl to the West and tulle to Egypt initiated a dynamic exchange between the two cultures. This interaction fostered a continuous exchange of ideas and materials, enriching both traditions through their mutual influence and adaptation. The forthcoming instalment of this series will examine the influential role of the Egyptian Asyuti in shaping fashion trends and styles, as it evolved and persisted through two major artistic movements: the Belle Époque and the Art Deco period in the West.